Eat more plant proteins

In Western countries, we eat too much animal protein, which can partially be replaced with plant protein. That is healthier for us as well as better for the environment and climate. Wageningen researchers are investigating protein sources such as legumes, duckweed, algae, and insects for use in our own diets or in animal feed. What do you think? Does a duckweed burger sound appetising to you?

In the Netherlands and other Western countries, we are consuming more protein than is good for us. In addition, we eat too much animal protein. In the 1960s, 40% of the protein that we ate came from animals. That has since risen to 60% and, as Stacy Pyett, programme manager of “Proteins for Life” tells us, these proteins come from meat, dairy, and eggs.

Adults require 0.8 grams of protein per day, with an average of 56 grams for men and 46 grams for women. However, according to RIVM, the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, the average Dutch person consumes 78 grams of protein per day. In order to return to the 40% animal protein consumption of the 1960s, this average must be reduced to 31 grams. The remaining protein should come from plants. “Animal protein contain all the essential amino acids,” says Pyett. “Not all plant protein sources provide the amino acids that we need, but these can still be attained by combining them properly.”

“This does not mean that we all have to start having a vegan diet. The most efficient food system contains a certain level of animal protein production.”

Soya from South America

Animal proteins are not just taking a toll on our health: intensive, large-scale animal farming is also damaging nature and the environment. “The environmental footprint of our food system is much higher than necessary. Producing 1 kilo of beef requires 20-25 kilos of grain. If people would eat soya instead of meat, 20 times less food would be necessary,” says Pyett. In Europe, we import soya from Brazil and other South American countries in order to feed our cattle.

High protein food

Animal proteins fit into an efficient system

This does not mean that we all have to start having a vegan diet. According to Pyett, the most efficient food system contains a certain level of animal protein production. “We can feed animals plant-based waste and food remnants and have them graze on less fertile pastures. We calculated that in doing so, we would be able to produce enough animal protein to supply people with 25 grams of it per day.”

Sharing knowledge

The growth of the global population is another reason to eat more plant protein. In order to ensure that people in developing countries are receiving enough essential nutrients, proteins need to be distributed more fairly. This requires international cooperation. Pyett: “The EU and Western societies can share their knowledge and technologies across the world. This would enable them to support local entrepreneurs in developing countries, who are growing crops that yield plant protein.” This could also be helpful in areas that have been affected by climate change, such as those that now experience dryer weather. For instance, protein-rich crops that are better equipped to handle drought could be cultivated.

“Circular agricultural systems in which nothing goes to waste are perfect for the sustainable production of plant protein.”

Tomatoes and eggs in a circular system

“Circular agricultural systems are perfect for the sustainable production of plant protein,” says Pyett. For example, in Mexico, many tomatoes are grown in greenhouses. The wastewater from the greenhouses is packed with nitrogen, which pollutes the groundwater if it comes into contact with it. However, nitrogen is also a fertiliser. This led researchers to realise that algae would be able to grow in the wastewater. “Algae only needs nitrogen and sunlight. If the algae is later dried, it can be used as chicken feed. Algae is high in omega-3 fatty acids and proteins which, in turn, results in chickens that lay eggs that are rich in omega-3. This creates a perfect system, in which nothing goes to waste,” explains Pyett. Another example are insects that feed on the residual food waste streams. These protein-rich animals can later be used in pet food.

Duckweed and broad bean milk

Protein-rich crops, such as algae, duckweed and legumes, can be used in new ways in food and animal feed. For example, duckweed is a promising source of protein. The plant produces six to ten times more protein per hectare than soya beans and it grows very quickly. However, there are other well-known sources of plant protein that can be used differently, such as broad beans. Once its characteristic, mildly bitter aftertaste has been eliminated, there may soon be a variety of broad bean milks and yoghurts on the shelves at the supermarket — right next to the duckweed burgers.

More variety

More variety

“We are moving towards a wider range of plant-based, protein-rich products for human nutrition. We are replacing rice with quinoa, spinach with duckweed, and beef with chickpeas.” says Pyett. That creates a greater variety of agricultural crops. Global crop production is primarily focused on a just a few core crops, including wheat, rice, maize, and soya.

Stimulating development

Before that can happen, scientists must research the related cultivation methods, food safety, and nutritional values. Only then can the industry begin developing new food products. The government can help stimulate the development of new food sources and products. “This is necessary, because the price of new products is typically higher. As such, nothing currently competes with soya as animal feed. It is produced on such a large scale in South America that it is extremely cheap, even after accounting for the transport costs required,” says Pyett.

Make vegetable proteins attractive

It is also important to make plant protein appealing to consumers. “There has been enormous growth in plant-based products and two thirds of the population identifies as flexitarian. However, meat consumption still needs to decrease,” adds Pyett. “People perceive the term “plant-based” as positive, and it is fantastic that being a flexitarian is now popular. But we still need to investigate how to encourage people to eat more plant protein.” The government can also play a role in this.

Ambition: proteins only from Europe

The Dutch government and the EU have already established ambitions which demonstrate their willingness to fulfil this role. By 2030, the Netherlands aims to ensure that half of the protein-rich resources used in the country will come from Europe and to limit that to exclusively European-produced plant protein by 2050. This is not just talk either: both the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV) and the EU have made funding available for research into achieving this and Wageningen is participating. Pyett: “Ten years ago, there was not much funding for this type of research. The transition towards using more plant-based protein has started, though it is still in its infancy.”

Mansholt Lecture on protein transition

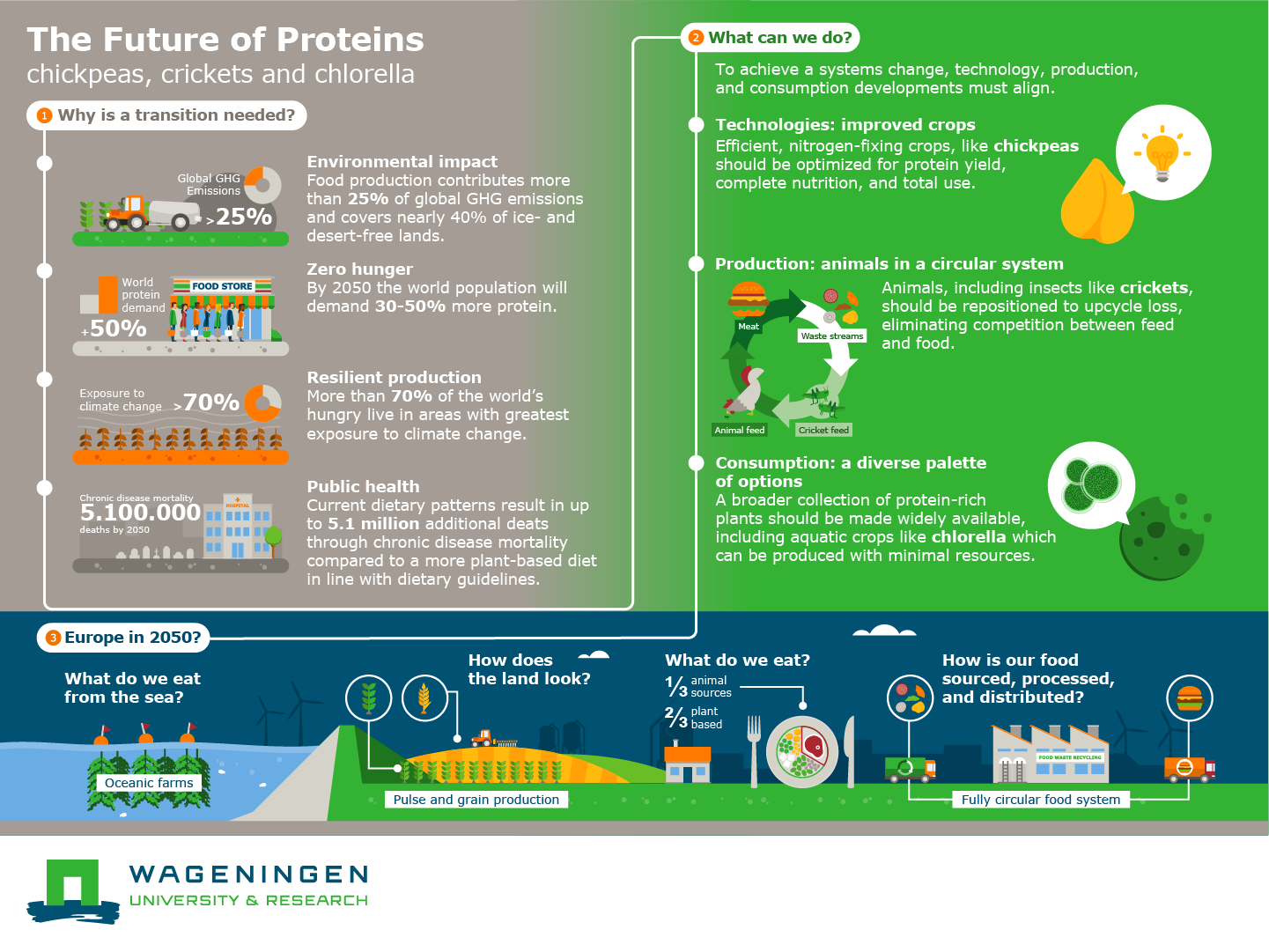

Wageningen University & Research is aiming for a future where protein production is sustainable, affordable, and healthy. A future in which specific combinations of plants, animals, and micro-organisms from both land and sea are adapted to local conditions, even in areas where resources are scarce. On 18 September 2019 in Brussels, the fourth edition of the Mansholt Lecture will focus on the future of proteins.

Mansholt brochure ‘Chickpeas, crickets and chlorella: our future proteins’

> Download the brochure

> Request a hard copy

Read more

- An article on consumers and the need to eat less meat.

- Wageningen research on plant-based proteins

- About the Mansholt Lecture on the protein transition in Brussels on 18 September 2019

- Video about the new generation of meat substitutes

- Read this article in Dutch

Hello,

interesting article, but the following is a bit strange:

Under the headline: “Eat more plant proteins”

I find insects as an example in the teaser…

(“In Western countries, we eat too much animal protein, which can partially be replaced with plant protein. That is healthier for us as well as better for the environment and climate. Wageningen researchers are investigating protein sources such as legumes, duckweed, algae, and insects for use in our own diets or in animal feed.”)

Best regards

Ulrike

You’re right Ulrike, insects are not plants but small animals. Good catch!

Hi, really great to see more practical examples of where our food systems need to go to become sustainable. Do you know if similar models / thinking exists for Africa and Asia? I ask as that’s the area I work on and would like to promote this discussion in the trainings we give at WCDI. Any links or suggestions are welcome!

Hi Thomas, We are definitely thinking about what solutions fit in Asia/Africa! On September 18th the Mansholt lecture giving the overview on protein transition will be held in Brussels and our booklet will become available. I think I understand you are a colleague, so you’re also welcome to contact me by email and we can have a cup of coffee and discuss.

Goodmorning,

Insects endangered species !? If so

why bring them into the Foodchain

All those people to be fed should be

motivated ..no more than 1 child..!

for the present, .. to be rewarded!

Instead we pain ourselves

how to feed 10/20 billion of our sort.

Its a shame ..half the population lives

in no condition at all… nevertheless we

are busy how much this or that to eat

until behind the comma …. .

have a nice day

Hello my name is Tatiana Gamboa I am a professor and researcher at the School of Public Health of the Universidad de Costa Rica. I am interested in doing a PhD and I really like the line of research that addresses healthy food environments and a sustainable environment. I would like to know if there is any possibility of doing the PhD in Wageningen, either the conventional doctorate or the sandwich type

Hi, Interesting and instructive article.

In my country, with a high consumption of animal protein, a large percentage of the population is suffering from cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Caring for food production and educating the population on a proper diet is reduced to a minimum, ie nonexistent.

come to the Republic of northern macedonia is great for research.

have a nice day

interesting topic because the whole world is going to suffer from climate change ,special my country south Sudan hot temperature remain and much desert is going to happen,so can help us which type of food shall eat in South Sudan, sit Duck or Fish,or beans/