Art as inspiration for science

Contrary to popular opinion, the scientific quest for knowledge is not a predictable and well-defined process. To make new discoveries, researchers need the freedom to be creative, fail, and learn by chance. There is an overlap with art in that respect. This is why Wageningen scientists look to artists for inspiration and exchange ideas about how to increase creative freedom.

There is this romantic idea of the scientist who has a Eureka moment and suddenly arrives at new insights. Another impression is that research only involves well-defined, formal steps. Neither of those ideas is correct. Creativity is very important in research, and there is an overlap with art in that respect.

“The connection with art can help to shift focus more towards the scientific process than the result.”

“Science and art are two different ways to make something comprehensible or conceivable. They both provide a perspective on reality,” says Biochemistry Professor Dolf Weijers. “From the outside, the research process looks very formal and the artistic process looks somewhat messy. But the scientific process can also unfold in an unpredictable way. Creative and associative thinking is very important for scientists to gain insight and make connections.”

Strange associations

“Scientists can learn a lot from artists,” says Weijers. “Association and creativity are central to art methodology. Those aspects require more attention in science as the creative process is the essence of science.”

The creative process must allow one to fail as well as discover things by chance. Physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming accidentally discovered the bactericidal fungus penicillin during a study of the staphylococcal bacterium in 1928. It was a great example of serendipity: discovering something valuable while you were looking for something else.

“Association and creativity are central to art methodology. Those aspects require more attention in science as the creative process is the essence of science.” Photo: Duncan de Fey.

“Researchers must be allowed to experiment. Failing and making mistakes is part of that. You must create an environment in which you can propose strange associations and ideas and where you may discover something by chance. You create this environment by looking differently at how you compose your team and what you stimulate in your team,” says Weijers. “To me, it has always been very natural to provide an opportunity for creative chaos. It attracts people that work the same way.”

The stereotypical view of what science is and does has been changing in a broader sense. “Luckily, there is increased attention to diversity and the different ways you can be a scientist.” It is no longer only about how many articles someone publishes, but also about what someone contributes to a team, education, science communication, and the social debate. “That cannot all be addressed in formal training, but you can stimulate this by looking to other disciplines such as art.”

Collaboration

Weijers and his colleague Joris Sprakel, professor of Physical Chemistry and Soft Matter, together with other Wageningen scientists and artists, have devised a plan to learn from each other and to exchange ideas. The idea, which has been delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic, is to create a platform where scientists and artists meet. Weijers stresses that he cannot speak on behalf of artists, but thinks that the continuous search for innovation, the cutting edge, will make science very appealing to artists.

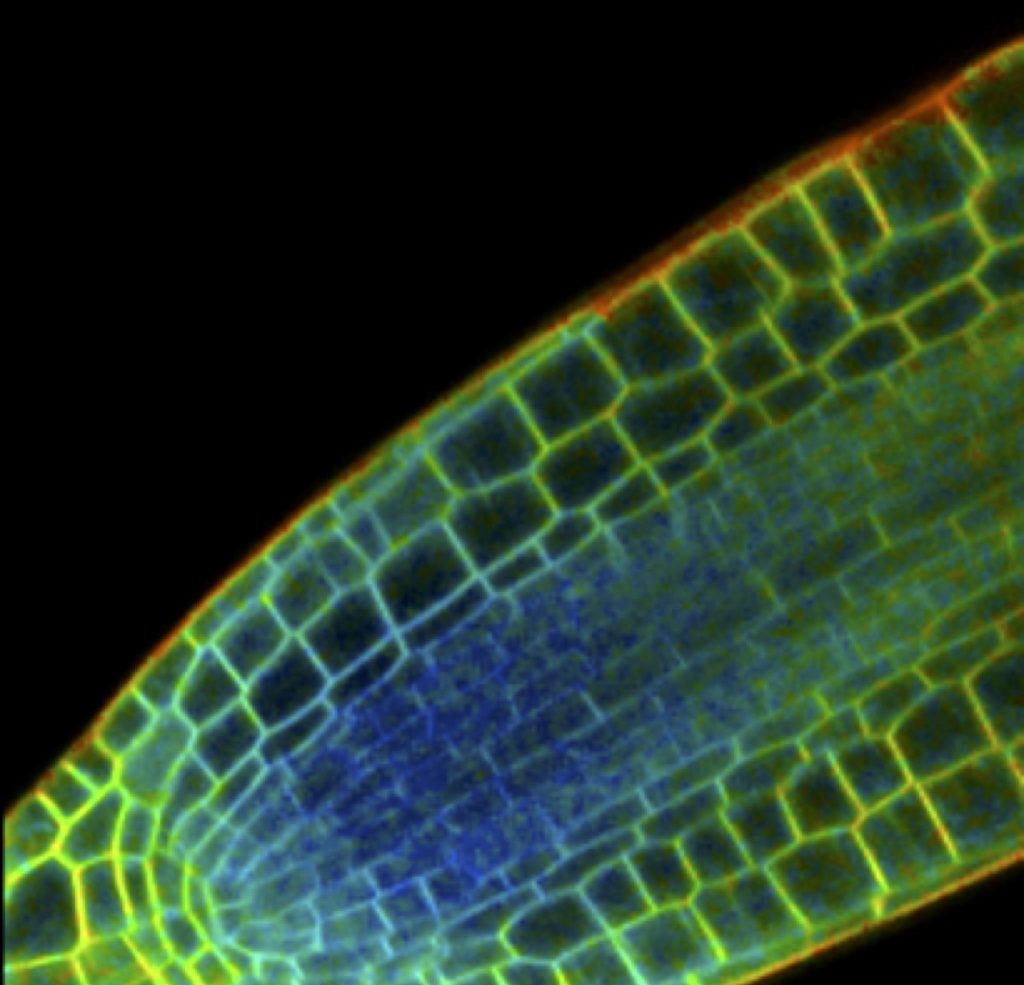

Forces in plant cells: In this cross-section of a root tip of the thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), a molecular sensor was used to visualise the different forces that act on the cells. The different colours each represent a different force. By Dr. Vera Gorelova, WUR.

“As a scientist, you use different methods, but it is equally about how you visualise your perception of reality, of the connections that there are. This is sometimes just as visual as art.” One example is the recent and special project in which Weijers and Sprakel measured the forces that act on plant cells, on a molecular scale. They revealed the results in the colourful image above.

Incomplete knowledge

What science and art also have in common is that they are topics of discussion in society. There are people who say that they do not value art and people who mistrust science, such as with climate change or the coronavirus. “It often creates the wrong impression because only the results of scientific studies are presented, and people do not have any insight into the process leading to discovery. As a scientist, you are criticised if you ultimately say that something is different a few years later. Then you are viewed as unreliable. But what is often poorly understood is that there are no final results in science.”

Every scientific finding is based on current knowledge. Incorrect insights or incomplete pictures are the key to arriving at more correct insights and more complete pictures. “That incompleteness and uncertainty are an uncomfortable reality for many people,” says Weijers. He continues, “The greatest thing that we as scientists can achieve in the coming period from a social point of view is to provide more insight into the scientific process so that incomplete and progressive insights can become an accepted part of knowledge acquisition. Personally, I think that the connection with art can help to shift focus more towards the process than the result.”

Opening of the 2021-2022 Academic Year

Crossing Boundaries is the theme of the online opening of the Academic Year at Wageningen University on Monday 6 September 2021. Scientists and artists explore the world around us in different ways. They both create new insights and objects by challenging and breaking the boundaries. In the process, they are affected by chance, failure, and the like. The online opening of the academic year is about how science and art inspire each other. Both are part of the broad public dialogue about our human future.

> More information and registration

Read more:

- Louise Fresco, President of the WUR Executive Board, about art inspiring science

- About research by Joris Sprakel and Dolf Weijers into how forces act on plant cells

- Read this article in Dutch

Lead image: the cellular compass of a liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha) visualised. The SOSEKI compass protein has been made visible in all cells (in yellow) and marks the corner of the cells that are directed towards the youngest parts in the centre. By Dr. Catherina Albrecht, WUR.