Digital nature conservation

What will nature management and preservation, biodiversity conservation, and nature research look like in the future? Traditional working methods require a significant commitment from organisations and their employees, such as site managers, researchers, and volunteers. They can now expect excellent support from unexpected quarters, including innovative technology such as sensors, camera traps, DNA analyses, drones, and artificial intelligence. These new instruments help researchers collect data that was unimaginable previously. North Sea seals are now equipped with digital data collectors to gain insight into their behaviour far into the sea and deep under the water. Innovation for nature conservation is the theme of the 101st Dies Natalis of Wageningen University & Research on 11 March.

Seals in the North Sea

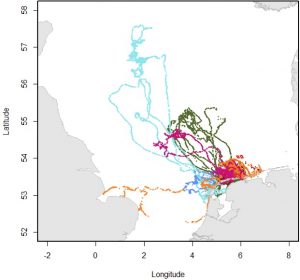

In their research into seals in the North Sea, researchers from Wageningen Marine Research and colleagues from other knowledge institutions such as NIOZ and TNO use tracking devices to chart the behaviour of these large mammals.

The diving behaviour of a seal with a tracking device. The period of pile driving is indicated with a green line (start) and a red line (end). Between 20:00 and 22:00, the diving behaviour of the seals differs from the periods before and after.

Human activity in the shallow North Sea is increasing rapidly. Construction, ship motors, sand extraction, raising beaches, and underwater explosions add to invisible sound pollution, which means that there are hardly any quiet areas in the North Sea. Relatively new is the construction of wind farms, which brings with it the source of loud underwater sounds. Pile driving the foundations causes sound waves that can be heard by seals more than fifty kilometres away.

What do seals hear?

Researchers Geert Aarts and Sophie Brasseur of Wageningen Marine Research focus on the behaviour of seals in the North Sea to measure the impact of the building of wind farms and ask whether this affects the population or its spread.

Geert Aarts: “We know that porpoises are particularly sensitive to high frequencies, while seals hear low tones very well. We compared their hearing spectrum to the frequencies of pile driving. It appears that seals are particularly good at hearing the far-reaching pile driving noise between 500 Hz and 1 kHz.”

This raises the question of whether this influences the animals: are they behaving differently, does it bother them, and can it cause changes in the population or its distribution?

The research team followed twenty seals during pile driving within a 70-kilometre radius of the activity. The researchers fitted the seals with a tracking device attached to their fur with glue, meaning that the transmitter will eventually be released during the annual shedding. The presence of the tracking device should not influence the animals, as researchers want to study their natural behaviour. The team was able to determine the exact start and end of a pile driving session, with up to 80 strikes an hour, and combine this information with the movement and diving behaviour of seals.

Change in diving behaviour

“We saw how the seal’s diving behaviour changed during pile driving”, the marine ecologist explains. While prior to the pile driving sounds, seals regularly dive from the surface to the bottom, about 30 metres down, in most cases their diving behaviour changes significantly during the pile driving. The seals with a tracking device sometimes don’t dive as often, and not as deep. “They stay at the surface a lot more. In other cases we see there is no change in the number of dives, but their swimming direction changes. And, interestingly, they don’t necessarily swim away from the sound, as it is hard to determine the direction of the source.”

“We registered a lot of different reactions in the seals, but the diving speed is clearly affected during pile driving”, says Geert Aarts. “Sometimes a seal at nearly 50 kilometres reacts, while a closer seal, at 10 kilometres, doesn’t react at all. But when we take everything together, we can determine that, on average, animals change their behaviour at 37 kilometres from the source of the sound.”

Smart watch

In the autumn of 2019, the first seals will be fitted with a sensor similar to a smart watch, which is fitted with a speedometer that can register the animal’s movements very precisely. Because the sensor is fitted right behind the head, the instrument will measure the head movements, such as when catching a fish, but also the flipper movements during swimming. This way, rest moments (no flipper movement) can be distinguished from swimming periods. These details provide more insight into the behaviour of animals, such as when and how they eat. Do they surface every time after catching prey, or do they catch multiple fish per dive? How does this change during pile driving or when there is a ship approaching, for instance? But also, if they are thinner, it is easier for a seal to dive, fatter seals will resurface quicker (and with less effort). How does this change during the period in which we follow them?

Read more:

Dies Natalis 11 March: information and registration

Dossier Nature Conservation