Draining and storing water due to climate change

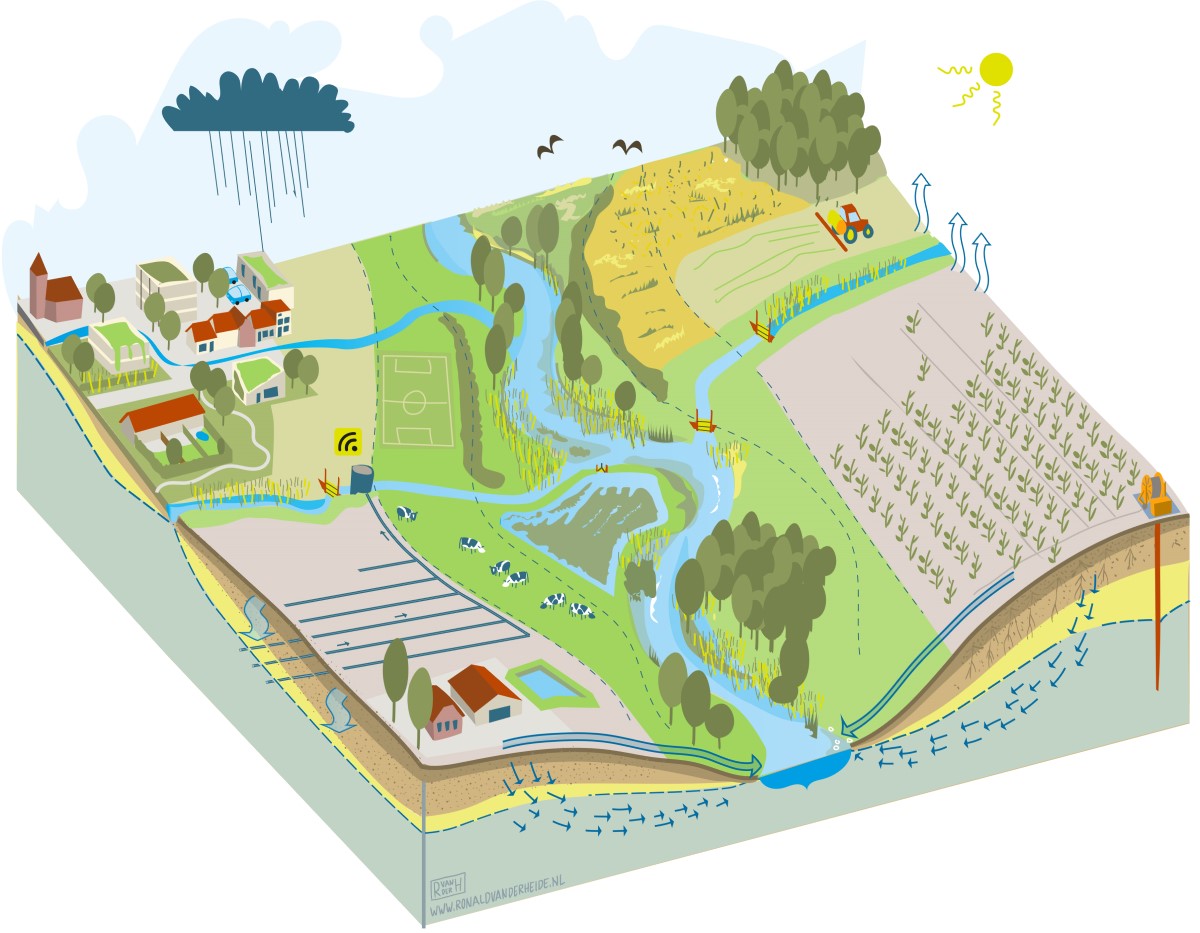

The Netherlands is designed for the rapid draining of superfluous rainwater. The dryer summers that result from climate change, however, also call for the storage of water. Wageningen researchers collaborate with water managers to discover what steps may be taken to increase water availability for agriculture and nature. For example: deploying deep-rooted crops, soil life or smart dams and drains. Want to know how the Netherlands can make the change?

“Each region has its particular problems, soil and hydrological circumstances, and its unique nature and agriculture. We design tools: different support systems and tools that can be deployed per individual region.”

‘We have known for a while that climate change means our country will be dryer, while at the same time having to deal with flooding through heavy precipitation. But, now that we have seen three consecutive dry years, it is easier to get attention focused on this issue’, says hydrologist-soil expert Mirjam Hack-ten Broeke.

‘The Netherlands is a delta, we have hardly ever faced water shortages. So, everything is designed to drain superfluous rainwater as fast as possible. This will have to change. We will have to work towards retaining water.’ In addition to drainage, which remains necessary due to extreme precipitation in heavy showers and the regular winter-related water surplus.

Due to climate change, the Netherlands increasingly experience long periods of drought, with the occasional downpours (Photo: Shutterstock).

Joining forces

‘Collaboration is key in making progress’, says Hack-ten Broeke. To determine what steps are needed, various universities and knowledge institutes, as well as water authorities and provinces, join forces. Following this, they search for solutions in collaboration with land-users such as farmers, businesses and nature managers. Together, they investigate how elevated sandy soils may be adjusted to climate change through the collaborative programmes Lumbricus and KLIMAP. Various methods may be deployed, ranging from technical and hydrological measures such as smart dams, to the use of deep-rooted crops and soil life such as earthworms.

The KLIMAP project

The KLIMAP research spans multiple years and focuses on a climate-adaptive layout of elevated sandy soils. It is co-financed by the top-sectors Agri & Food and Water & Marine. In addition to seven water authorities, STOWA, three provinces and several businesses, knowledge institutes are also involved: Wageningen University & Research, Radboud University, Deltares, KWR, Louis Bolk Institute and KnowH2O.

> More on KLIMAP

The impact of the dry summers is most keenly felt on the elevated sandy soils of Noord-Brabant, Overijssel, Gelderland and Limburg. The sandy soil does not retain water as well as clay soil. Moreover, the elevated sandy soil is entirely dependent on precipitation for its water supply. In other areas in the Netherlands, rivers and the IJsselmeer also add to the water supply.

Deep-rooted crops such as grains, hemp and flax adapt high sandy soils to make them more resilient to climate change (Photo: Shutterstock).

Wet springs

‘The way rural areas are designed will have to change, and agriculture must follow.’ If you retain more water in the winter, this leads to wet circumstances in the spring. This is something farmers are not accustomed to, as they generally require dryer conditions for ploughing and fertilising. ‘We believe they will eventually benefit from retaining water for the dry summers, but the entire agricultural system will have to adapt to wetter springs. Something easier said than done.’

Online workshops and concluding symposium ‘Lumbricus’

The Lumbricus research programme runs from 2017 to 2021 and focuses on climate-proof soil and water management in elevated sandy soils. How do you safeguard sufficient water for agriculture, nature and recreation? How do you prevent flooding? What combination of measures are available, and how do these affect yields and nature value? How can you improve collaboration with residents and users?

The project partners share their insights and provide practical tools in three digital workshops and a concluding symposium.

02-02-2021, 10-12 hr: Workshop 1 What is a climate-proof system?

11-02-2021, 10-12 hr: Workshop 2 What tools do we use?

18-02-2021, 10-12 hr: Workshop 3 What building blocks do we recognise?

03-03-2021, 10–12.30 hr: Concluding symposium with various speakers

> Information and registration (in Dutch)

Dynamic process

The researchers, water authorities, governments, agricultural and other businesses collectively consider the transition towards a climate-proof layout. ‘We discuss what the area should look like in the future, and what is needed to reach that goal. These discussions are repeated as new insights arise, and new plans and agreements are reached. This discussion going back and forth between the present and the future is a dynamic process. It is not a roadmap to get from A to B, but rather development paths that support policies as they are developed.’

Calculating effects

KLIMAP’s predecessor is the Lumbricus programme, Latin for earthworm. This programme is now drawing to a close but will continue in KLIMAP. Both are multidisciplinary projects that scrutinise soil management, water balance, nature and governance. In addition to soil experts and agriculture experts, governance experts are also involved.

Much has already been learned about the instruments and tools that researchers, water authorities and policy-makers have at their disposal. ‘These have also been improved. For example, in the models that calculate the impact changes in water management or climate have on agricultural yields and nature. Insight into these effects is essential for water management.’

Better understanding

“Participative monitoring” is also part of Lumbricus. This means that the farmers concerned conduct their own measurements of, for example, water levels on their land, and share this information with each other and with the researchers. ‘This fosters an understanding of the issues faced by the water authorities.’

With weirs and climate-adaptive drainage or sub-irrigation, farmers can determine how much water they retain or discharge (Photo: Shutterstock).

Based on these findings and weather models, farmers can decide how much water to drain or retain, says Hack-ten Broeke. ‘We aim to have farmers operate the smart dams and climate-adaptive drainage or sub-irrigation systems themselves. These new techniques are under development by project partners KWR and en KnowH2O.’

No blueprint

Once new measures are implemented, monitoring how they develop is crucial. ‘Do the measures lead to the desired results and how may a solution in one location be scaled up to span the entire region?’, says Hack-ten Broeke. She stresses that each region faces its own particular problems, soil and hydrological circumstances, and its unique nature and agriculture. ‘In KLIMAP, we design tools: different support systems and tools that can be deployed. But there is never a universally applicable blueprint.’

Subsidence and salination

Even the lower regions in the north and west of our country are increasingly impacted by drought. Thus, researchers and water managers plan to launch a project similar to KLIMAP, focused on the lower-laying areas that face issues such as subsidence and salination in addition to flooding and drought. ‘There too, multiple research institutes and local governments will work towards a future-proof perspective for the short-term and the long-term.’

International summit on climate adaptation

The international ‘Climate Adaptation Summit’ is to take place on 25 and 26 January, online. World leaders and local stakeholders discuss how we can best adapt to a new, more extreme, climate. In 24 hours, there will be contributions and live-streams from different time-zones across the globe. Like many other knowledge institutes, Wageningen University & Research is not directly involved but contributes indirectly. Wageningen contributes to adaptation strategies and seeks solutions to combine climate change and climate adaptation, for example, through climate-smart agriculture and climate-smart cities. Often based on knowledge of nature.

The Climate Adaptation Summit builds on the work done by the ‘Global Commission on Adaptation’, established by the UN in 2018. During the international online summit, participants will draft an ‘Adaptation Action Agenda’, to reach concrete steps and alliances.

> Mere information and registration

Read more

- Background article “Hold that water!”

- Project by Water Resources Management: Coping with Dutch drought

- On the KLIMAP project

- The website of Lumbricus and a video on the Lumbricus project

- Dossier Climate and Water

- Dossier Flooding

- Dossier Climate and Soil

- Programme Sustainable Water Management

- Read this article in Dutch