Faster plant growth through more efficient photosynthesis

As a result of climate change, the amount of arable land is shrinking, while the world population is on the rise. This is why Wageningen researchers are studying ways to reduce the required soil area of crops. They have discovered that some plants make better use of light for their growth than others. By using available knowledge on the natural genetic variations in this photosynthesis process, plant breeders may be able to develop crops that use soil, water and nutrients more efficiently. Do you consider this a suitable method for dealing with the limitations in available farming soils?

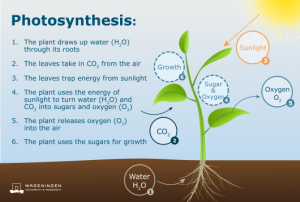

Plants obtain their energy from sunlight. With this energy, their chloroplast converts water and CO2 into oxygen and glucose. Glucose feeds the plant and helps it grow. This process is called photosynthesis. ‘Photosynthesis has existed for some two million years, which is why scientists assumed it was fully developed and plants were operating at their maximum efficiency level,’ states Mark Aarts, professor of Plant Genetics.

Plants obtain their energy from sunlight. With this energy, their chloroplast converts water and CO2 into oxygen and glucose. Glucose feeds the plant and helps it grow. This process is called photosynthesis. ‘Photosynthesis has existed for some two million years, which is why scientists assumed it was fully developed and plants were operating at their maximum efficiency level,’ states Mark Aarts, professor of Plant Genetics.

This is far from the truth. Plants appear to use no more than between 0.5 and 1 per cent of the available sunlight. Some plants, however, such as grey mustard (Hirschfeldia incana) make far better use of the sun than others. Aarts: ‘Grey mustard is a type of cabbage. We all know the Dutch expression “growing like a cabbage” to describe fast growth. Perhaps cabbage contains a substance enabling it to photosynthesise well.’ Grey mustard shares this trait with desert plants. ‘When it rains in the desert, plants must sprout immediately and grow at top speed. Otherwise, they will not make it. They have a short life-span of a few weeks,’ Aarts explains.

“We believe we may be able to breed plants capable of using up to one and a half per cent of the available sunlight instead of the current half per cent. That is a tremendous improvement.”

Genetic variation

‘It is fascinating to discover there are plant species that are much more effective in their photosynthesis, as was the case in our research on grey mustard,’ says the Plant Genetics professor. He and Plant Physiologist Jeremy Harbinson started to research this phenomenon a decade ago. With the help of students, PhD candidates and postdocs they not only discovered that some plant species deal with photosynthesis differently, but they also found that individual plants of the same species vary in this regard. Some plants are just better at it than others. By utilising the natural genetic variations, they have now managed to improve the photosynthesis process.

Swapping chloroplasts

Aarts and his colleagues have studied thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), an essential subject in many plant sciences studies. The Wageningen scientists managed to replace the chloroplast from one thale cress plant with that of another, without any change to the chromosomes’ genetic material. Thanks to this new method, researchers can compare original plants with plants that have ‘new’ chloroplasts. Some of the new combinations yield plants with improved growth compared to the original combinations.

Thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana). Wageningen scientists managed to replace the chloroplast from one thale cress plant with that of another, without any change to the chromosomes’ genetic material.

‘This new insight allows breeders to develop crops that provide a higher yield,’ says Aarts. ‘We believe we may be able to breed plants capable of using up to one and a half per cent of the available sunlight instead of the current half per cent. That is a tremendous improvement.’

Crops

As a result of drought, silting and heavy rainfall caused by climate change, the availability of arable land decreases. This means we have to be thriftier with the soils we have. Furthermore, the world population is expected to rise to almost 10 billion by the year 2050. ‘One way to ensure there is enough food is to have plants with a higher yield.’ Countries in Africa still offer considerable production improvement potential if better seeds, fertilisers and enough water are used, the professor indicates. Europe not only already has high agricultural production, but this continent also produces for other continents. ‘Therefore, it is important that we develop crops capable of more efficient use of space and resources.’

Mark Aarts: we all know the Dutch expression “growing like a cabbage” to describe fast growth. Perhaps cabbage contains a substance enabling it to photosynthesise well.’

More energy

Why doesn’t nature create plants that use sunlight more efficiently and grow at the same speed as the mustard plant? ‘That is indeed something we would like to know. In nature, this high level of photosynthesis must have some kind of disadvantage. We suspect that a fast-growing plant such as this encourages the specialisation of plague insects,’ Aarts replies. However, in farming, plagues can be abated through a combination of resistant species and healthy farming practices.

Much fundamental research is still needed before we reach that point, however. ‘Photosynthesis provides the energy needed for the plant’s growth and development. We don’t know exactly how the plant uses this energy. A higher rate of photosynthesis not only causes the leaves to grow larger, but could also cause longer and thicker roots, or more abundant flowering. Plants use sunlight in different ways, that are not always obvious.’

Current research

To increase their knowledge of photosynthesis, Wageningen researchers carry out different studies. Aarts is involved in an EU photosynthesis project studying genetic variation in millet, tomato and maize. ‘We expect to find significant differences, just as in the thale cress.’

The Phenovator produces very precise measurements of the photosynthesis of 1440 plants several times a day. Photo: Tom Theeuwen

Other research focusses on attuning plants to the light. When there is abundant sunlight available, part of it is not used for photosynthesis but radiates as warmth in a process called non-photochemical quenching, Aarts explains. ‘A beneficial process to prevent sunlight from damaging the photosynthesis proteins. But on partially cloudy days, plants tend to err on the side of caution and use this ability to lower the rate of photosynthesis. This causes the process of photosynthesis to be far less efficient than it could be.’ How exactly does this process work, what proteins are involved, and where does the energy go? Aarts’ colleagues are trying to find answers to these questions through extensive research funded by the NWO.

Changing light

NWO also funds non-photochemical quenching research carried out by a future PhD candidate supervised by Aarts. The NWO recently accepted a major research proposal. This will allow Aarts to collaborate with colleagues from Wageningen, Utrecht, Amsterdam and the United States and ten breeding companies, to investigate how plants react to changing light circumstances. For example, if a cloud obscures the sun, or the weather shifts between cloudy and bright sunlight during the day, or as a result of shade cast by nearby plants. ‘We want to know what genes are responsible and if there is genetic variation in this regard. Following that, we want to see how these genes can influence the reaction of plants to these changes in circumstances and reduce non-photochemical quenching, without damaging the plant. In a greenhouse, for example, this protection mechanism is redundant,’ states Aarts.

University birthday

Wageningen University & Research viert op 9 maart 2020 haar 102e verjaardag, ‘Dies Natalis’ in het Latijn. Dit jaar is het thema ‘Illuminating science for transitions.’ De nadruk ligt op het belang van basiswetenschap in het domein van de levenswetenschappen. Donald Ort, hoogleraar Biologie aan de Universiteit van Illinois, bespreekt zijn fundamentele onderzoek naar fotosynthese. Verder lichten drie jonge wetenschappers een tipje van de sluier over hun wetenschappelijke werk in Wageningen.

Informatie en aanmelden

Read more:

- Article “Catching more sunlight in a plant”

- Background information on the importance of photosynthesis research

- On genetic variation in photosynthesis

- On all Wageningen research on photosynthesis

- Read this article in Dutch

Podcast:

Researcher Jeremy Harbinson talks about photosynthesis in the podcast “Makkelijk Praten” (in English)

So interesting

Wonderful stuff. Could increasing the rate of photosynthesis be deployed to combat global warming? I imagine, doubling the rate of photosynthesis in corn, and introducing that trait in all corn could convert a lot of CO2 to O2. Am I dreaming?

This may indeed be one of the possibilities to consider. Especially if we need or want to convert our current fossil carbon-based economy to a biobased economy, it would be a great help if we could fix much more CO2 in plants than we do now. If we can do this, and we can use the biomass made with it for a long term purpose, eg. hemp fibers in construction, it could indeed help in reducing CO2 levels.