Vaccines against RS virus in infants and calves

In the Netherlands, some two thousand young children are hospitalised each year with a pulmonary infection caused by the RS virus. Globally, the RS virus is second only to malaria as the leading cause of infant mortality. A genetically similar bovine virus shows a comparable pathology in calves. Wageningen researchers have set up an infection model that is utilised in developing a safe, effective vaccine for children and calves.

“ During our research, we visited a pediatric ICU. This really gave us a sense of purpose ”

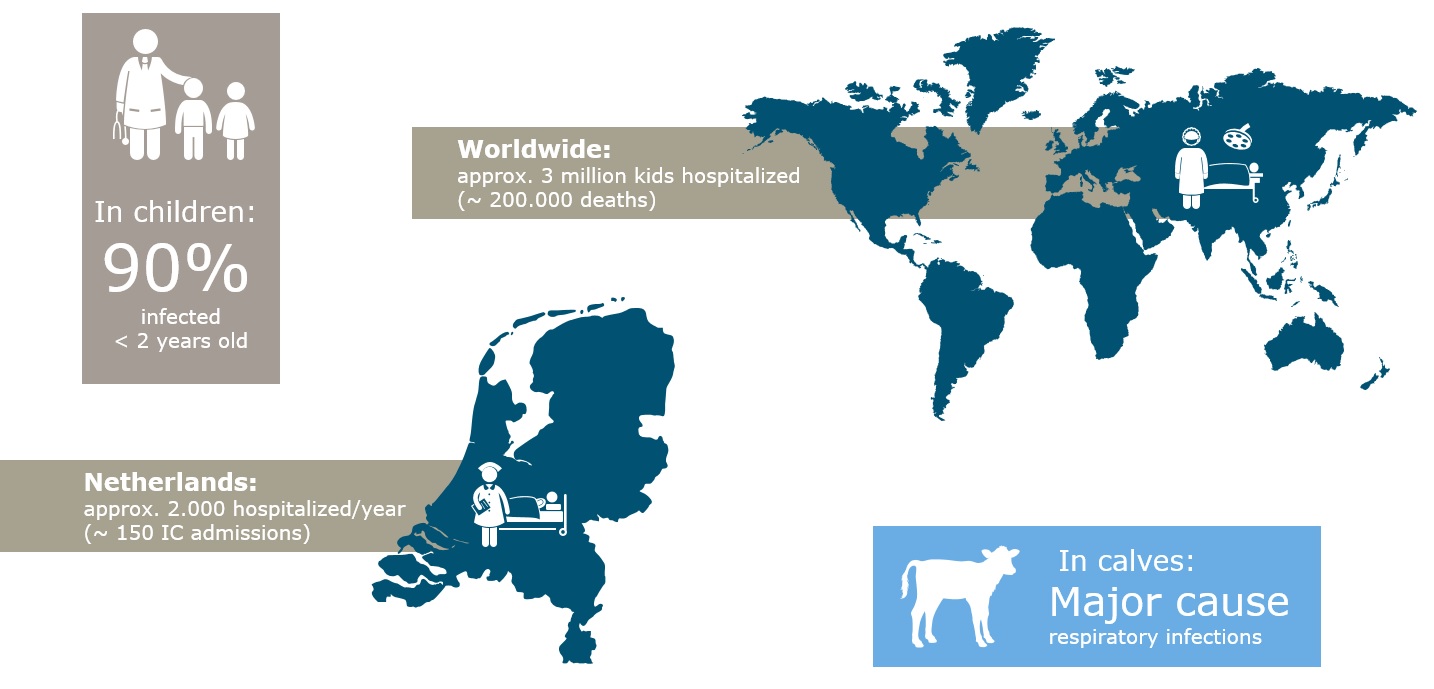

In winter, many babies are committed to pediatric ICU’s and hooked up to ventilators because of pulmonary infections caused by the RS virus, the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). Most adults and children infected with this virus, that can also cause repeat infections, experience mild cold-like symptoms. But infants up to six months, and vulnerable babies, for example, prematurely born or suffering from heart conditions, may contract a severe pulmonary infection as a result of this virus. In countries lacking accessible medical care, the virus may be fatal. Globally, RSV is the cause of death in some 200,000 infants a year. In the Netherlands, approximately 2000 babies are hospitalised, of which between 150-200 are admitted to a pediatric ICU.

Besides causing problems in young babies, the RS virus has been increasingly recognised in recent years as a serious threat to older people with impaired immune systems and any underlying conditions. There are figures showing that the impact of RSV in the elderly is similar to the impact of seasonal flu.

The impact of the RS-virus.

Pulmonary infection in calves

The human RSV that occurs in people is closely related to the bovine RSV in cattle. Bovine RSV occurs on almost all cattle farms in the Netherlands and the resulting pulmonary infections can cause major problems and significant economic losses, especially in calf farms. Calves under six months of age, in particular, can develop a severe respiratory infection with a fatal outcome in one in five cases. There is a wide variety of pathogens and bacteria that cause or exacerbate pulmonary issues. How large the contribution of the bovine RSV is, is not always known, because an extensive diagnostic is not always run.

‘By the way, this virus is not a zoonosis, children cannot get sick from the virus in calves or vice versa,’ stresses Rineke de Jong, veterinary researcher and project leader.

Less susceptible mice

Because of the severe course of RS infection, research to develop vaccines has been going on for years. ‘You cannot immediately test a vaccine developed for humans in children or the elderly. The standard approach is to test the vaccines in an infection model in rodents. However, in this case, the host and virus are not attuned. Because rodents are naturally less susceptible to the human virus, an infection is not representative,’ De Jong explains. However, infecting calves with the bovine RSV yields a representative pathology; they show the same symptoms as children.

Rodents such as mice are not naturally susceptible to the human RS virus and are therefore less suitable as laboratory animals (Credit: Shutterstock).

Antibodies

In recent years, much research has been done on the genetic composition of viruses. On their surface, the human and bovine RSV have a very similar protein particle. ‘Many developers of human vaccines use precisely that similar protein particle in their vaccines to trigger an immune response in children’, De Jong says. Her research shows that this type of vaccine also works in calves. ‘If you treat calves with this type of vaccine against human RSV, they generate antibodies that can also protect them against the bovine RSV.’

Vaccines

The developers of human vaccines can use the results in calves to substantiate the viability in children, the researcher continues. ‘If calves are protected, this would strongly suggest that the vaccine would show a similar result in children.’

The infection model that was developed in Wageningen evaluates the vaccines for calves and children and could help demonstrate the vaccine’s safety. ‘In the sixties, a vaccine was marketed for children, in which the entire virus had been deactivated using formaldehyde. Some children infected with the RS virus subsequently appeared not only to lack immunity but to develop worse symptoms because their immune response had been derailed. Some infants even died. Thus, vaccine developers are cautious regarding safety, and want to be absolutely certain that the virus prompts the correct response.’

As developing an effective and safe vaccine for young children with an incompletely matured immune system remains a challenge, vaccine developers have in recent years also focused on developing a so-called “maternal” vaccine. This is a vaccine that can be given to women during pregnancy. It boosts the mother’s immune response to the RS virus and passes protective antibodies through the womb to the baby. As a result, the baby is better protected against RSV during the first months after birth.

In early 2023, the first two RSV vaccines became available for vaccinating the elderly (over 60 years old) and one of these vaccines has now also been registered for vaccinating pregnant women.

An improved antibody therapy has also already become available in 2022, which can preventively protect babies for about 100 days. “The RS virus is seasonal. With this drug, babies can be protected through the winter with one injection in autumn, so this is a great development,” De Jong responds.

Developing a working vaccine against the RS virus for young children remains a challenge (Credit: Shutterstock)

But the need for an effective vaccine for young children remains. ‘Like the antibodies the baby gets from the mother, the antibodies of this therapy are not produced by the immune system itself. They are broken down after a while. A vaccine activates memory in the immune system, allowing it to make its own antibodies. That gives more long-term protection.’ In addition, vaccinating children may help protect the elderly, as they often contract an RS infection through their contacts with younger children.

The human and the bovine variant of the RS virus are similar: A human RS virus vaccine protects calves from the bovine variant of the virus (Credit: Shutterstock).

Medication and treatment

When it comes to the RS virus in children, the focus is not only on prevention, but also on medication and treatment methods. The Wageningen researchers may also use their infection model in calves to investigate whether antiviral drugs can reduce the severity of disease symptoms. This has advantages and disadvantages. A baby is 4 kilos, while a calf soon weighs 60 kilos and thus needs much larger doses of the drug. ‘It is less attractive to make such large doses of an expensive antiviral drug. On the other hand, because a calf is so big you can measure and sample all kinds of things from it and take enough blood for the study.’

Reducing mucus production

Several years ago, De Jong and her colleagues carried out research on the RS virus and the pathogenic process in collaboration with the Amsterdam Medical Centre. ‘Children had trouble breathing because they produced a lot of mucus. The doctors wanted to know whether a treatment for cystic fibrosis might offer relief. So, Wageningen scientists tested this in calves. They saw a positive effect on the composition of the mucus and the pathogenic process. De Jong: ‘It is not a solution, but it did offer the small patients some relief. This research taught us much about the pathogenic process and where to search for an effective treatment. We are eager to do fundamental research, but getting funding is a challenge.’

The RS virus can cause serious respiratory infections in young babies (Credit: Shutterstock).

Scepticism

When Wageningen started studying human vaccines against the RS virus approximately a decade ago in the calves-model, the researchers were met with skepticism, De Jonge indicates. ‘Human and veterinary researchers barely know each other.’ The connection between these two worlds was not established until recent years and is limited at that. The increasing focus on One Health, which resulted from zoonoses such as avian influenza, Q-fever and the novel coronavirus, has caused this connection.

Veterinary vaccines

Fortunately, vaccines for calves have been on the market for some time, but there is still room for improvement there too. ‘It would be good if the veterinary and human research worlds could find each other more in this too, and we would like to contribute to that.’

Read more

- Short explanation of research on the RS virus in children and calves

- More in research on the RS virus in children and calves

- Read this article in Dutch