Can Circular Agriculture Be Practised Outside the Netherlands?

Really, I am a fan of circular agriculture. I truly believe that we can find sustainable solutions if we all commit ourselves to developing sustainable production systems. Finding solutions to produce enough food in a way that is good for our planet. I therefore talk enthusiastically about the examples that are available.

For example, strip cropping, a system in which the crops make optimum use of the nutrients available in the soil, simply because they have different rooting depths. In strip cropping, less or even no pesticides are needed: insects do not develop into a pest because the crop in the next strip is not ‘tasty’ enough. Meadow birds return because there are enough insects to feed their young. And still, there is enough food produced to be competitive with current production systems. In short, a system with great potential.

Can it be done in Africa?

And when I have told such an enthusiastic story, I am invariably asked the question: can circular agriculture also be practised in other countries? And my answer is always: yes! And yes, it is possible in Africa too, although I also know that some of my (former) colleagues claim otherwise. I see and read the stories that explain why it cannot be done, so I thought, let me counterbalance that and show with an example from Ethiopia that it really can be done. Moreover, it also significantly improves the living conditions of those farmers who currently must survive on food aid.

Principles of circular agriculture

Let us return for a moment to the basic principles of circular agriculture. It starts with the idea that nature, food and agriculture are valuable and connected. And then there are several starting points:

- Use all available land to produce food for people.

- Use the side streams that arise from the production and processing of food for animals, soil improvement or the bioeconomy.

- Make sure you can recycle side streams safely.

- Limit the input of fertilisers and pesticides.

If you use these principles and want to build a resilient system, you automatically end up with a system that is much more diverse than the current large-scale monoculture, as we have in the Netherlands but also in the US, for example. If you ask me, agricultural development in the world should not focus on efficiency and scale increases, but on diversity, nature inclusiveness, technological development and perhaps a change in the way we address “scale”.

Recycling in Ethiopia

With these principles in mind, let us look at Ethiopia and specifically at the farmers who depend on food aid through the This is an assistance programme for the two million poorest farming families in the country. These farmers often have about 0.25 to maximum 0.8 acres of land at their disposal. On this small piece of land, food must be grown to provide enough food for a whole family for a year. This is almost never possible. So, one can safely assume that these farmers are not interested in a story about preserving biodiversity and soil health. Their primary objective is to ‘make a living’, a principle that I also often hear from the Dutch farmer.

On the other hand, these Ethiopian farmers hardly have the financial means to buy pesticides or fertilisers, for example. Furthermore, it is good to know that in Ethiopia the law stipulates that fertilizer is available in 50 kg bags, no other size of bags are available. 50kg is a good amount for farmers with at least an acre of land, but far too much for a field with the size of a quarter of an acre.

Besides, with the risk of a lost harvest (due to climate change), these farmers cannot bet on just one crop. They prefer a system in which several crops can be harvested. Ethiopian farmers also receive advice from the government on how to make compost. Unfortunately, the method prescribed by the government, compost pits, requires a lot of labour because compost is constantly being transferred from one hole to another.

Desolate or good basis?

At present, the system described above is a hopeless one. A system in which a lot of money is invested annually to support people. In addition, it does not improve the quality of the living environment; soils produce a kind of yield, despite minimal input, and therefore slowly deteriorate in quality. Yet I dare say: this system is a good starting point for circular agriculture. The question is: how do we transform this system into a production system that produces enough food, is resilient regarding climate, uses the available side streams, does not need pesticides, and only requires minimal input of artificial fertiliser?

My colleagues Remko Vonk and Amede Tewodros picked up this challenge and started working in 40 districts that receive support from the PSNP programme in Ethiopia. In the REALISE project, financed by the Dutch embassy, they looked for interventions that could increase the productivity of these farmers by making optimal use of the natural resources they have. The preconditions: climate resilience and risk diversification. The goal: food security.

A fresh approach: the one-timad package

They focused, amongst others, on increasing production through intercropping, fast-maturing crops, labour-saving measures, seed availability and increasing agricultural diversity. They di discusthe size of a bag of fertiliser with the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture. Based on earlier work by Wageningen University & Research in Ethiopia, we know that the recommended amount of fertilizer in Ethiopia can be halved, provided it is combined with compost.

Very exceptionally, the participants in the REALISE programme were given permission by the ministry in Addis Ababa to adjust the packaging of fertiliser and seeds to the needs of a field of a quarter of a hectare. And the farmers were advised to supplement this with compost. This was the first ever affordable production advice package for these small farmers. In Amharic, a quarter of an acre is one timad. This is how the one timad package was born. System innovation also received attention: youth employment, production advice in an affordable package and diversity in nutrition. In a period of two years, they reached over 40,000 farmers.

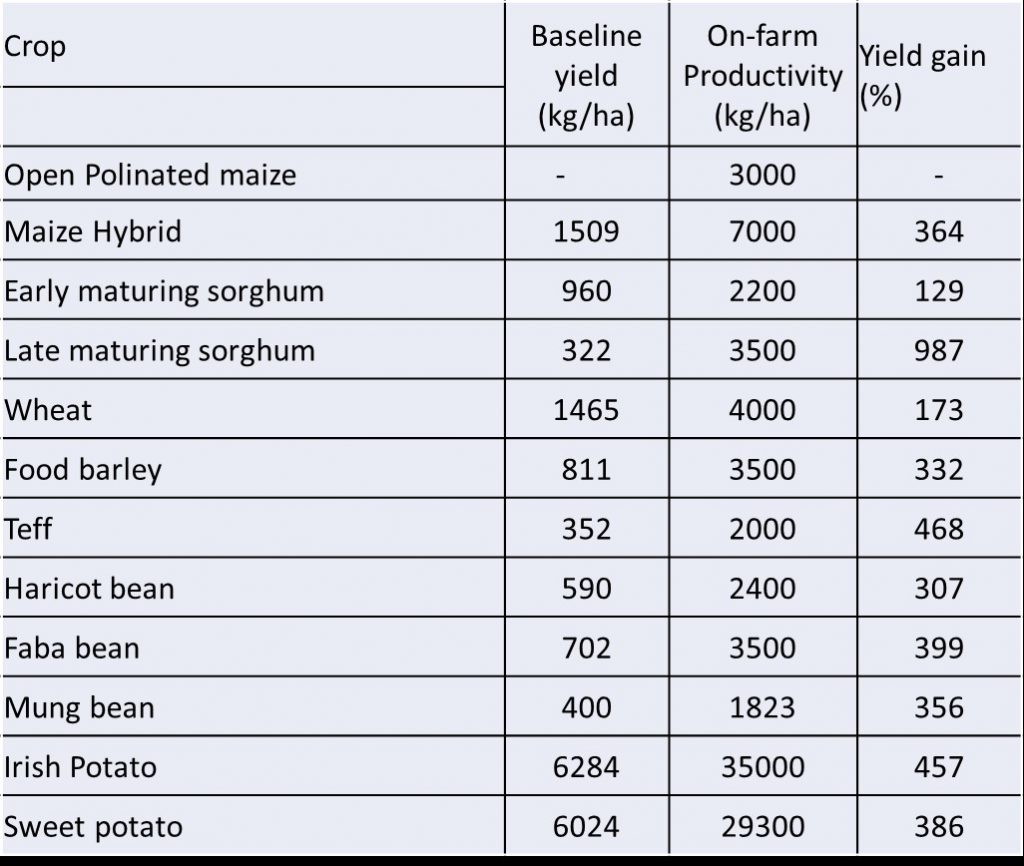

The results are more than impressive. Crop yields were quadrupled. Farmers not only had enough food, but also a greater diversity of food and the means to invest in the next harvest. A very important result is that not only the farmers, but also the Ministry of Agriculture is convinced of the one timad approach. The Ministry is now amending the law to make fertiliser available in the smaller pack sizes.

Harvest data collected from over 40.000 farmers in the PSNP regions in 2019 and 2020. The last column shows the impressive gains in crop yields.

Harvest data collected from over 40.000 farmers in the PSNP regions in 2019 and 2020. The last column shows the impressive gains in crop yields.

And what else?

Personally, I am impressed by what REALISE has achieved. This circular farming approach considers farmers’ limited purchasing power and increases the efficiency of land use. However, in this system, artificial fertiliser remains to be needed, in addition to compost. After all, we want the soil to remain healthy, and that includes soil fertility. In this system, many factors are important in the choice of crop varieties. For instance, the length of the growing season, water requirements, response to manure and disease resistance are just as important as taste, colour, ease of cultivation and processing. All these factors together provide a region with excellent agricultural diversity, which in turn is a good basis for (soil) biodiversity.

In short, this example proves that the principles of ‘circular agriculture’ can also be applied in Africa and give farmers food security. However impressive the result, we are not finished yet. The Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture is looking for a validation of the dosage, composition, and production methods of compost. The next step is to scale up, so that this knowledge reaches the more than 8 million people who now depend on food aid from the PSNP programme. I am very curious: what will the Ethiopian landscape and society look like if all this succeeds?

Images: Amede Tewodros

Join us in designing a circular bio-based and climate smart society. Go to Circular@WUR.

Would you like to know more about how the REALISE project has changed the lives of farmers? Visit the REALISE facebookpage to read testimonials and see more photo’s.

Would love to.discuss the possibility on how to.make the dessert in Sudan . more Green than yellow, with respect for.nature and circular economics