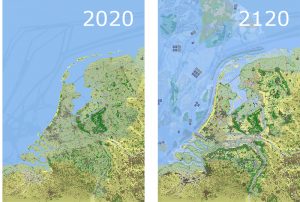

The Netherlands in 2120

Our country faces major challenges such as loss of natural areas, urbanisation, dry summers and flooding due to climate change. With all this in mind, Wageningen researchers have been examining the role that nature might play in renewable energy, town planning, agriculture and flood risk management. They have drawn up a 2120 map of the Netherlands, so that we will be in a better position to prepare for the future. What do you think the Netherlands will look like a hundred years from now?

Ecologist Martin Baptist told us, ‘Our motto for how we would like the Netherlands to look in 2120 is “a green vision rather than a nightmare”’. He joined Tim van Hattum, programme leader Green Climate Solutions, and other fellow Wageningen researchers from a wide range of disciplines in considering the future of the Netherlands. What will our country look like in a century’s time if we choose to make it one where food, energy and flood risk management are organised in a sustainable way? A country in which there is enough housing, and yet room for agriculture and natural areas?

Visit the WUR website for a detailed map

Green towns and cities

Could the map of the Netherlands for 2120 be called idealistic? ‘We haven’t opted for a wildly visionary image that sees us abandon half of the Netherlands to the sea and live on terps. That won’t be necessary in a hundred years. Our vision is fairly conservative. We want to continue protecting the Netherlands against rising sea levels with dikes and dams, reinforced dunes and additional foreshores. We really wouldn’t want to give up our historic cities,’ says Baptist.

The cities will be greener in 2120 than they are in 2020.

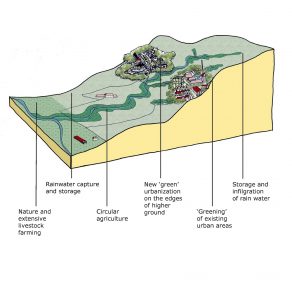

However, existing towns and cities will become greener. In summer, urban heat islands are created in cities. ‘There is already an urgent need to introduce trees, shade and greenery.’ What’s more, greenery is able to absorb more water from heavier rainfall. In order to house everyone, there will be residential developments on the elevated sandy soils of the Veluwe region and in Brabant. In Baptist’s opinion, urban and natural areas will be developed in harmony with one another and their futures interwoven. ‘More greenery is coming to the cities, and our cities will spread out among the greenery.’

Agriculture and natural areas

If it were up to the researchers, agriculture would be concentrated in the most fertile areas of North Holland, Zeeland and the Flevopolder. Agriculture will be circular, extensive, and more nature-inclusive. In coastal areas where the groundwater is no longer fresh but brackish, farmers will grow crops that are resistant to salt water, for instance certain potato and vegetable species and nutritious species of seaweed and algae.

“The spatial planning of the Netherlands is going to undergo a complete change. We can add a new dimension to it. We have based the 2120 map of the Netherlands around nature-inclusive solutions. What we believe in is preserving what is good and creating the beautiful.”

‘Wildlife conservation areas will be more strictly safeguarded, and at the same time nature will be used for coastal protection, to absorb flooding and to improve the living environment. The low-lying peat bogs that are currently settling and releasing CO2 will no longer used for building or as farmland. Instead, the peat will be made wetter so that it will once again be able to store carbon.’

Food, energy and water storage

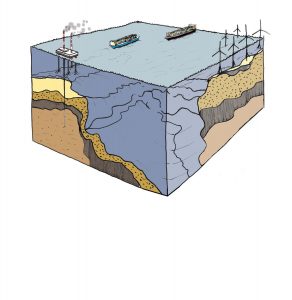

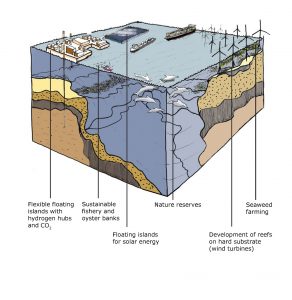

‘We occasionally forget that most of the Netherlands is made up of water,’ says Baptist. Besides the North Sea, we have the Wadden Sea, the IJsselmeer, the Delta and the rivers. These vast bodies of water are important in terms of such things as the food they supply and the transition to renewable energy. Renewable energy can be generated in wind farms, particularly on the North Sea and on floating islands of solar cells. Baptist goes on to explain: ‘We are going to turn the IJsselmeer into a storage area for a high river discharge, as we will be unable to drain off this water directly into the sea when the sea level has risen by 1.5 metres. An additional bank will be added to the IJsselmeer, and a fixed water level will be maintained between this and the mainland to create a passage for shipping. In the middle section, the water level will be dynamic, making it possible to manage peak discharges.’

The North Sea as it looks in 2020 and how it might look in 2120.

Centralised direction needed

The 2120 map was devised by a large group of researchers at Wageningen. ‘Agronomists, ecologists, social scientists, economists, people who understand flood risk management and changes in rivers. At Wageningen we have in-house expertise in all of these disciplines,’ says Baptist. The researchers are now in talks with governments, water boards and conservation organisations about their ideas.

The government is still working on the National Environment and Planning Strategy (NOVI), the Delta Programme, the National Climate Adaptation Strategy (NAS) and a new national conservation strategy. The 2120 map can be aligned with this. Baptist underlines the fact that all this needs direction. ‘In recent decades, the provinces and local authorities have increasingly had to shoulder the responsibility for spatial planning. Consequently, the policy has become too fragmented. Spatial planning needs to be returned to central government control, and there needs to be an overarching strategy.’

Creating the beautiful

According to Baptist, there is an internationally growing social movement calling for solutions to climate change, for climate adaptation and for the protection of endangered animal and plant species. ‘In the long term, the spatial planning of the Netherlands is going to undergo a complete change. We can add a new dimension to it. We have based the 2120 map of the Netherlands around nature-inclusive solutions. What we believe in is preserving what is good and creating the beautiful. This is the direction we need to take.’

Read more:

- About the plans for the Netherlands in 2120

- Longread about nature-based solutions

- Research into nature-inclusive solutions

- Read this article in Dutch

The Netherlands is a develop country. Dutch Govt. will do everythying planwise even in any kind of climate change situation. I think they will success and nothing to loss.

I wish and pray to Allah for every success of the Netherlands.