How does the sea fit into the circular bio-economy?

Authors: Saskia Visser, Tammo Bult, Simkje Kruiderink

Merely transitioning to circular farming systems is not sufficient for the sustainable production of enough food for the global population. We must develop a fully integrated food system, that includes marine food production as well as land-based food production. Only with a fully integrated foodsystems we can avoid land-based production solutions inadvertently impacting the seas, or vice-versa.

Martin Scholten, managing director of the Wageningen University & Research (WUR) Animal Sciences Group (ASG), described Wageningen’s research ambition regarding an integrated food system at the “Our Oceans Conference” in Oslo last fall. He indicated that the WUR research agenda will focus on an optimal, climate-smart and nature-inclusive usage of biomass from both healthy oceans and soils. The emphasis will lie on studying food production in interconnectedness with nature from a more holistic approach to water and food, both locally and globally.

Food web at sea is more efficient

How will an integrated system linking sea and land work for fisheries, the crustacean sector and seaweed production at sea? Prof. Jaap van der Meer, marine ecologist at WUR, recently conducted a comparative study of food systems on land and at sea. He proved that the foodweb – and with it, the natural food production system – on land differs fundamentally from that at sea.

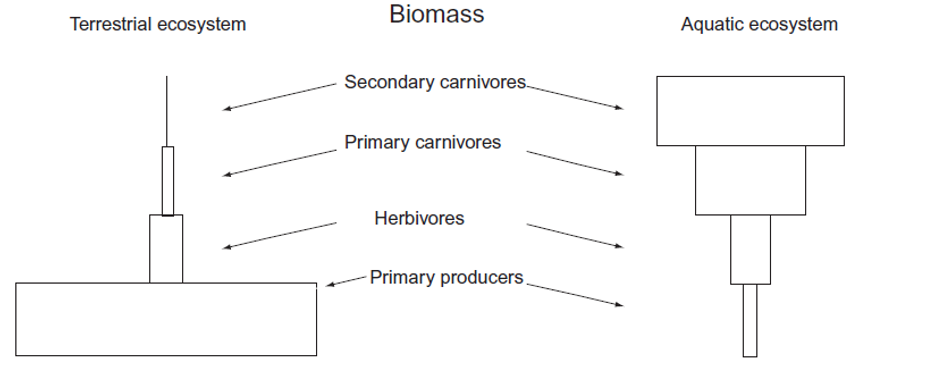

In both systems, sunlight is converted into plant-based biomass (primary production). Further along in the production chain, this biomass is processed by plant-eaters and meat-eaters, and thus, form the basis for human nutrition. In every step of these food chains, energy and materials are lost, producing ‘waste’ and CO2. These losses are naturally higher on land than in the sea. This allowed for such a significant efficiency increase resulting in higher food production at land.

At sea, this is different. The food chain at sea is naturally very efficient, and much longer than on land. Unlike the land-based food chain, the sea-based chain does not follow the pyramid model. On land, there is lots of biomass, fewer plant-eaters, and just a small amount of meat-eaters. At sea there are relatively few algae producing biomass, which are directly transferred into plankton and many more abundant biomasses, crustaceans along the coast and fish in deeper waters. In the seas, the main predators (fish) are readily available. At the same time, the land offers vastly more plant-based materials (such as rice, maize and grain) and plant-eaters (such as cattle, sheep and goats).

Opportunities for sea-based food are primarily found at the base of the foodweb

What conclusions can we draw from these insights into food production on land and in the sea? First, an awareness that our food is obtained from interconnectedness and combination of original primary production on land and in the waters. That is why we choose an integrated approach that includes both land and sea. Thus, we must consider the balance between the nutrients from land that reach the seas though river flows, and the nutrients we bring on land in the shape of fish, crustaceans and seaweeds, both as food and animal feed.

Van der Meer’s insights mean that “opportunities for more food from the sea” are primarily found at the base of the marine food web. The lower trophic levels close to primary production: crustaceans, seaweeds and algae. With regards to fish, choices are to be made. Sea-based production cannot be easily increased without adding nutrients, as the food chain is already very efficient, and the primary output is mainly dependent on sunlight and the availability of nutrients.

If we wish to continue to eat fish in a sustainable way, we will have to make choices, rather than seeking ways to increase production, just as we must for land-based production. For example, we could choose the most valuable fish with the least negative impact on the marine ecosystem. Fishers would then choose quality and a discerning narrative for a limited market, supported by a robust business model.

Knowledge development for sustainable marine production

When put this way, Van der Meer’s insights are logical and straightforward. But transitioning from the current stand-alone system to a more integrated food production system gives rise to a multitude of questions. Some are obvious, such as the question of how many nutrients originate in rivers, the atmosphere, and how they interact with the surrounding waters? And what portion thereof ends up on our plates through the food chain? What improvements can be made by closing local nutrient cycles, for example, in crustacean cultures in coastal areas? Are nutrients in the sea best used for food production (crustaceans and fish) or as a raw material for bioplastics and energy (seaweed, for example), or nature?

Besides, there are many more complex issues. What opportunities does an integrated approach open up for spatial planning in coastal areas and at sea? What choices do we, as a society, want to make in this regard? By earmarking space for fisheries, for the breeding of crustaceans and cultivation of seaweeds and by smarter usage of the available nutrients? And what about humans increasing their consumption of seaweeds and shellfish, how will the harvesting thereof impact the rest of the ecosystem?

It is interesting to consider what nature might gain from taking the marine ecosystem as a point of departure. What is the ideal ratio between biodiversity/nature and food production? And what is the maximum sustainable yield that can be achieved?

Finding Answers together

This new perspective in food production at sea demands a new knowledge agenda, with the corresponding means. The North Sea is relatively small. If we want to initiate significant changes based on this perspective, we need to collaborate at a global level.

Wageningen Marine Research recently took the first steps in this regard. In keeping with the WUR’s strategic plan Finding Answers Together, Tammo Bult, Wageningen Marine Research’s managing director has invited a group of international marine researchers* to discuss the meaning of these new insights and build new partnerships. Furthermore, he strives to generate a rough research agenda in collaboration with this research collective and to create a substantive link with primary production on land. The thus generated insights will then be shared with policy-makers at a national and international level. This way, Farm to Fork, the Green Deal and the food security policy of the FAO/UN can be fed by science.

*among others: Livar Frøyland – IMR, Erik-Jan Lock – IMR, Hanne Digre – SINTEF, Gunvor Oie – SINTEF, Ragnhild Dragøy Whitaker – NOFIMA, Hans Polet – ILVO, Klaas Timmermans – NIOZ, Geert Wiegertjes – WUR, Johan Schrama – WUR, Tammo Bult – WUR, Marnix Poelman – WUR, Jaap van der Meer – WUR, Simkje Kruiderink – WUR