The learning trajectory of information literacy

In order to be successful in their academic studies and future careers, students need to learn how to deal with (scientific) information and how to use it ethically. Annemie Kersten is instructor in information literacy at WUR Library. I interviewed her to talk about the skill of information literacy and how you can teach it.

Why is it important to teach Wageningen students to become ‘information literate’?

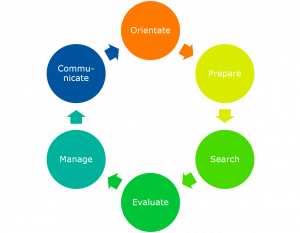

It is easy to get overwhelmed by the amount of scientific and other information available today. Information literacy is the academic skill to deal with this situation: it helps in every stage of a scientific project, from knowing what you are looking for (by formulating a good research question), to developing strategies to find information. Information literacy skills also help you to choose the best resources and use these in an organised and ethical way, in order to avoid plagiarism and copyright infringements.

The competency areas of information literacy, adapted from the SCONUL 7 Pillars of Information Literacy

What we see is that students mostly use Google or Google Scholar, simply because of the ease of use. But they often don’t know that the Library subscribes to many high quality databases that are great tools to find and filter scientific information. Also, students’ knowledge about referencing and plagiarism often leaves room for improvement.

What is the role of the Library in information literacy education?

In a nutshell, the Library provides education and learning materials in information literacy to Wageningen students, and to the teachers and coordinators of study programmes. This is the core business of the Library’s education team of which I am part.

In many BSc study programmes, we teach information literacy as part of specific courses and specific searching or writing assignments. In MSc study programmes, we contribute as (guest) teachers to MSc thesis paths, scientific skills training, or distance learning masters. We also have our own comprehensive MSc course of 1.5 ects that students can take. PhD candidates have their own course, Searching and organising literature, which is more advanced and includes individual instruction and help in creating systematic, comprehensive searches and setting up literature alerts.

A relatively new development is to offer a learning trajectory for information literacy in study programmes.

Tell me more about this learning trajectory for information literacy.

We wanted to connect more effectively to the learning process of students by offering them the right information at the right moment in their studies. This is why we started to develop a learning path or trajectory in 2016. The ultimate aim is to ensure that all BSc students reach a similar level of information literacy at the end of their studies. This is necessary to assure that MSc students from different backgrounds start with about the same level of information literacy at the beginning of their programme.

We are working with teachers, programme directors and study advisors to embed a learning trajectory for information literacy education in a number of BSc programmes. Education in information literacy is then offered to students more gradually during the course of their studies. Examples are Nutrition and Health, and Management and Consumer Studies.

The ultimate aim is to ensure that all BSc students reach a similar level of information literacy at the end of their studies.

What level of information literacy does a student need to have after his or her first year, bachelor, and master?

It is hard to give a straightforward answer to this question, because each student has his or her own learning path. But to help get a grip on this matter, we discern four different levels of information literacy, labelled A, B, C, and D. Generally speaking, level C is sufficient for students at the end of their bachelor’s. At this level, students are able to identify and select the right information sources for a scientific project, construct a systematic search, and to cite and reference sources in a correct way, using different citation styles when needed. They are also acquainted with the scientific publishing process.

In our discussion with teachers and study programme directors, we use a matrix of different learning goals and accompanying learning activities for students. These help to identify which level of information literacy students should have at the end of a course, or at the end of the study programme, and to choose suitable learning activities.

Do you provide learning materials for those not following your courses?

For individual students who want to develop, or refresh, their information literacy skills, we maintain and develop a number of interactive online modules. These modules serve as learning material in our courses and can also be used effectively for self-study. All of the Library’s modules have a Creative Commons (BY-NC-SA) license that allows others to share, use, and adapt our modules on condition that use is for non-commercial purposes and the material is shared under the same conditions.

How can study programme coordinators and study advisors learn more about integrating information literacy education in their study programmes?

The best way is to first go to our webpage for teachers and then to get in touch with me or one of my colleagues at the Library.

See also: