Does localising food value chains contribute to food system resilience?

This is part 13 of a blog series on food systems. This article was written by Deborah Bakker, Gonne Beekman, Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters, Haki Pamuk, and Seerp Wigboldus. It is based on the article “Localising value chains and food system resilience: A systematic exploration.”

Interest in exploring the benefits of localising food value chains is on the rise. This is fuelled by global crises — notably the COVID-19 pandemic. Many civil society organisations, international research institutes, and various national governments have put the topic of ‘local’ versus ‘global’ high on their agendas. This involves addressing questions regarding values and qualities to be realised through food system transformations, such as food security, resilience, fairness, and food sovereignty. However, the ‘local’ versus ‘global’ discussion is quite controversial. Therefore, we aim to demystify the subject, by unpacking the real goals and effects from localisation policies.

Vulnerable to global shocks

Since the 1980s, African economies have become rapidly integrated into global value chains. During this liberalisation process, largely fuelled by the World Bank and IMF, food value chains in Sub-Saharan Africa became closely intertwined with global food markets. African agricultural exports of primary products, such as coffee, cocoa, nuts, flowers and cotton, increased. Also, the production of food crops has expanded steadily, but food imports—such as rice from Asia—supplement regionally produced food.

“The framework that we briefly present here, can help in assessing the potential impact of localisation policies on food system outcomes in a relatively simple, yet structured and sound way.”

The recent outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted critical vulnerabilities of global food systems. These systems proved to be closely interlinked. In the wake of this global crisis, local and regional value chains were not able to adjust and respond effectively to sustain food security. To better cope with inevitable future global or local shocks – whether related to health, climate, or geopolitics – it is therefore necessary that policymakers and other key stakeholders get a better understanding of the vulnerabilities of their food systems and of opportunities to strengthen their resilience.

Shortening value chains

One pathway to achieve increased food system resilience is to opt for more localised and shorter food chains where food is processed and consumed close to where it is produced. Related transition processes need to be informed by an integrated perspective on food system performance. That includes economic performance, but also outcomes such as food and nutrition security as well as concerns regarding fair distribution of benefits, national food sovereignty, and environment. However, empirical evidence on implications of localisation of value chains are scarce, and so are methodologies to assess these implications.

Does localising value chains contribute to food system resilience?

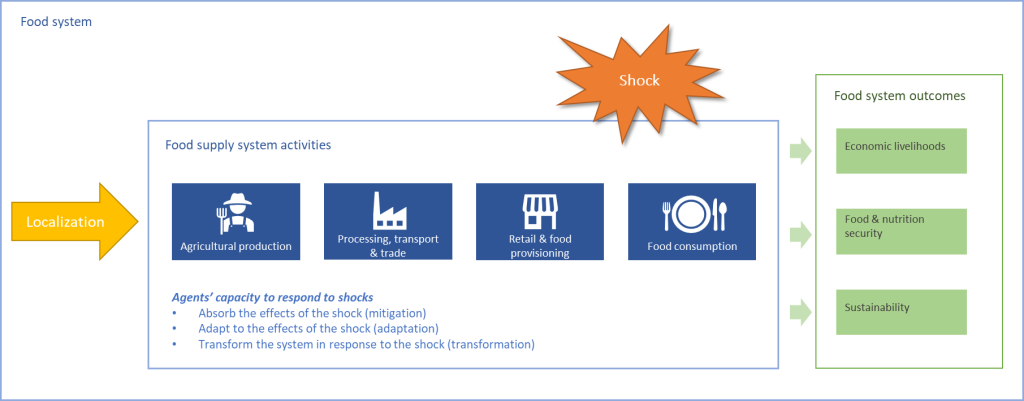

With the above in mind, we developed a framework to find answers to the following questions: Does promoting localisation of food value chains really enhance the capacity of food systems to deliver desired outcomes in the face of shocks and stressors? What might be the impact of policies that aim to localise food value chains, on food system actors (through the activities they undertake), and food system outcomes? And what might be trade-offs within the food system (see Figure 1)?

Figure 1: Effects of localisation on food systems actors and outcomes.

Application of the framework

Now, let’s apply this framework on the case of localising rice value chain in West-Africa, to illustrate its use and outcomes. West-African governments see localisation of rice production as a way to reduce consumer dependency on rice imports from Asia. We identified three main trade-offs related to such policy.

In the first place, localising the West-African rice value chain would directly affect various food system activities. For example, smallholder producers would expand their production and input providers and transporters would expand their businesses. However, as rice prices will increase due to import tariffs, consumers might reduce rice consumption and shift to other food crops instead. Secondly, localisation would leave the rice value chain less vulnerable to global shocks (in the wake of a global financial crisis, there would still be stable local availability of rice). However, the value chain might become more vulnerable to local shocks such as drought, pests, or domestic political unrest. Finally, impacts on food system outcomes will likely range from positive to negative. Whereas due to localisation, consumers might pay higher prices for local rice compared to imported rice, smallholder producers’ and midstream businesses’ income levels will improve due to increased economic activity.

These results offer input for more detailed follow-up research on potential trade-offs. Furthermore, the results help policymakers in agenda setting and in deciding on appropriate instruments to mitigate the potential negative effects of localisation policy.

Open food market in Matadi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Photo: Skinstorm / Shutterstock.com.

Evidence-based assessments

The framework that we briefly presented here, can help in assessing the potential impact of localisation policies on food system outcomes in a relatively simple, yet structured and sound way. Using this framework contributes to more transparent food system governance by informing stakeholders on anticipated effects of localising a food value chain on actors, their capacity to respond to shocks, and outcomes. These insights help create transparency regarding who might win and who might lose, as well as policy options that could mitigate potential negative effects.

In follow-up research, we would like to further improve the framework and the interpretation of findings by applying it on cases in a variety of contexts and by validating results with stakeholders and key-informants with in-depth knowledge about the context. Visualising results from the analysis framework in a dashboard could help policy makers in assessing the potential effects of policy interventions.

In short, the presented assessment framework contributes to the need for gathering evidence on the impact of localising food systems on food system resilience. The current broad interest in this topic combined with the fact that many related questions remain unanswered, calls for further in-depth studies on the interface between localisation and resilience of food systems.

Read more:

- WUR Research Theme: Food Systems

- WUR Research Programme: Food Security and the Value of Water

- Applying a Food Systems Approach: the key to Zero Hunger in 2030

- A food system approach leads to food security