Start of the Saba Bank expedition 2018

Header image: Saba Bank during our expedition in 2015 (photo: David Stevens).

We (Lisa Becking, Tobia de Scisciolo, and me) are ahead of the rest of the team to try out techniques that we want to use on the Saba Bank and to refresh contacts with our coral restoration project (www.rescq.eu) counterpart on Statia, STENAPA (St. Eustatius National Parks).

Erik, Lisa and Tobia

Statia: the Golden Rock

As always, coming to Statia, as the locals call St. Eustatius, feels like visiting an old friend. The people are always incredibly friendly and we always are sorry to leave and always promise ourselves ‘next time I will stay longer’. But research funds are limited and you want (need) to be as efficient as possible with the money you get. Statia has an impressive history and has a claim to having once been one of largest harbours in the Northern Hemisphere. It was called the Golden Rock and the island is littered with historical artefacts from canons and huge anchors under water to slave beads. There are old drawing where dozens of ships were anchored in front of the city of Oranjestad.

Historical building on St. Eustatius

Murphy is just around the corner

It was good to be a week earlier in the Caribbean because, as every researcher knows, Murphy is just around the corner. Murphy’s law states: ‘Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong’. It is undeniably the least-tested scientific hypothesis, which each scientist believes without questioning. It’s especially true for underwater cameras and accessories such as flashlights. Luckily the rest of the team is not leaving till Friday and they may get just in time a new flashlight, which I need for my research. Hopefully, Murphy is now on his way and will not return again.

Expedition Saba Bank

Arranging a trip like this with 17 researchers on board is always a big undertaking. There is lots to take care of and the responsibility kind of hinders me to enjoy these field expeditions as much as I should. You worry about the planning of the research and the safety of the people, since diving on the Saba Bank is not for the lighthearted; however, we are in good hands with the dive crew from the Caribbean Explorer (how fitting the name!), a live-aboard diving company that normally caters to tourists.

We organise an expedition to the Saba Bank once per 2-3 years, and for most of the rest of the year I’m sitting behind my computer at Wageningen Marine Research analysing data and writing reports and publications. So yes, we do enjoy these trips. They are everything we wished to do when we signed up to become a researcher; they are what keeps us motivated (against the ever increasing administrative burden). As long as I can do my research, I don’t mind.

Research needed for conservation

The data we collect and the knowledge we gain from our research is dearly needed and used by many. Especially in a time when coral reefs are so much under pressure, it is important to inform the public about the status of these unbelievably beautiful underwaterscapes. They are under siege, they are suffering, but there still are beautiful places that are recovering. I believe the Saba Bank is such an area. It’s far away from the polluting influences of the mainland or big islands. It does suffer from climate change that causes bleaching, but the corals are healthy and can recover from these episodes of extremely warm water if given enough time.

Bath tub

The Caribbean Sea is like a big bathtub and is becoming more and more filled by nutrients that flow in from the mainland and from the surrounding islands. My fear is that we won’t stop this process in time, so that even the most remote places such as the Saba Bank will become affected. We assess the status of the Saba Bank this year by looking at a lot of different aspects. I hope you will enjoy the contributions by all the participants.

Largest nature area in The Netherlands

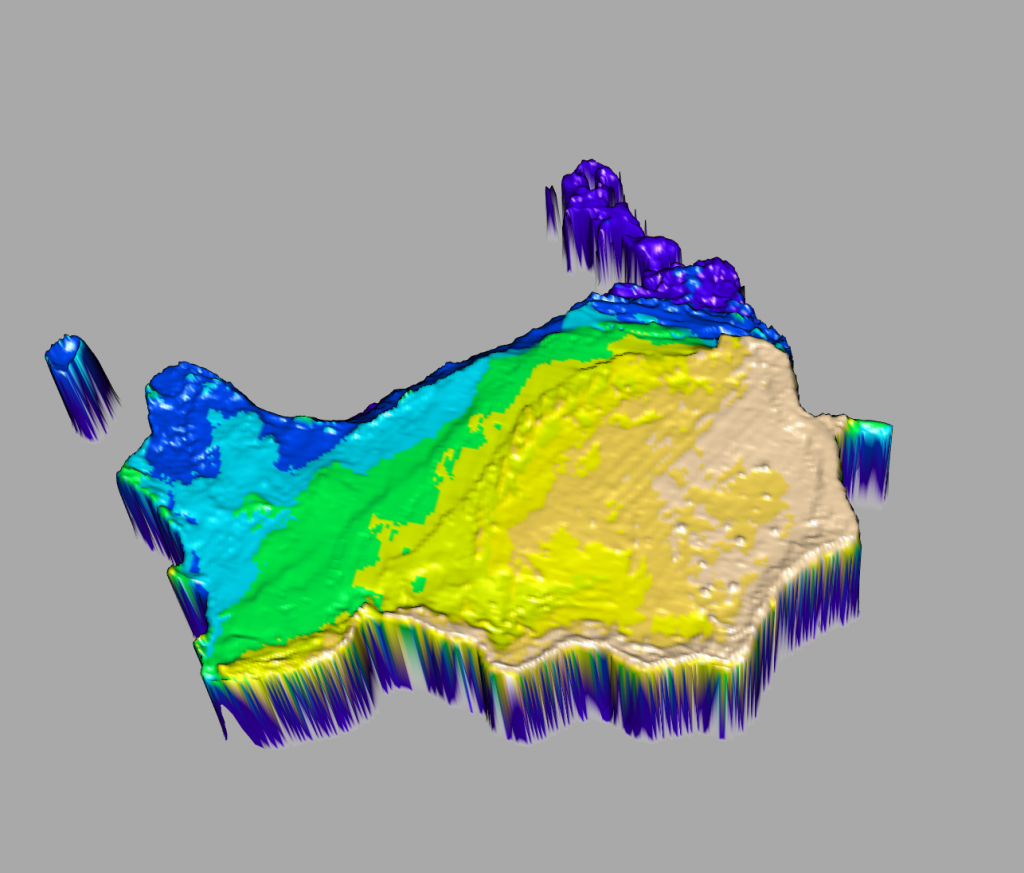

Saba Bank, a 1000 m high table seamount, as large as the province of Utrecht.

The Saba Bank is undeniably the largest nature area of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (>2400km2) and has the biggest coral reef area of the whole Caribbean Netherlands. Its biological diversity is recognised by the international community through the Convention on Biological Diversity, which gave it the status of an EBSA (an Ecologically or Biologically Significant Area, read more about it on this page). I’m grateful for the opportunities I get from Wageningen Marine Research and to the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for funding our research on the Saba Bank.