Gymnastic popcorns

Have you ever stand in front of the microwave waiting for your popcorns to explode? Have you ever recorded a slow motion video of a kernel popping? Science is always around us and again is not magic what makes popcorn to pop but it is this time pressure who rules this pop.

What are popcorns made off?

Pop-corns are a variety of corn kernel which has the capability of expanding when heated. This corn variety can jump and make a “pop” sound when cooked. However, a successful pop requires the physical properties of popping. These popping conditions are related with the breakage of the outer hull of the kernel, also known as pericarp (Virot & Ponomarenko).

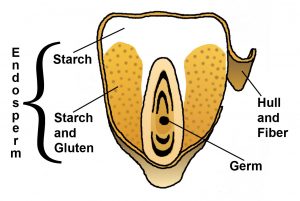

Popcorn kernels have a soft endosperm which gives nutrition and a hard endosperm also called pericarp which surrounds the soft endosperm.

The soft endosperm of a kernel is mainly made by starch (a sugar molecule) and it also contains water (Figure 1). The pericarp is mainly formed by fiber and cellulose (string of sugar).

What triggers the POP?

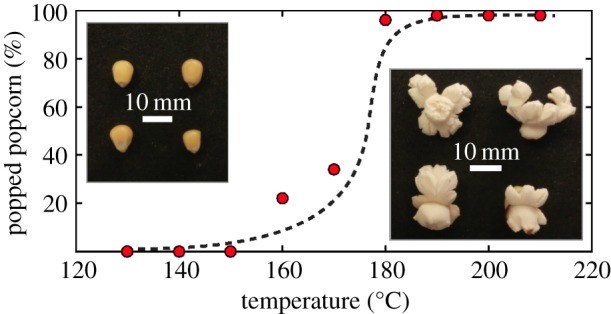

Before being nice white popped corns they are hard kernels. These kernels have strong hulls that contain a starchy endosperm with a moisture content ranging from 8.95% to 17.12% (Karababa). When the popcorns are heated and the temperature exceed the 100°C, the water content starts to boil. Therefore, the water reaches its thermodynamic equilibrium at the vapour pressure.

Once this critical vapour pressure is achieved, the pressure of the steam is that high that it forces the hulls of the kernel to break.

As you might imagine, the higher the temperature, the higher the amount of popped popcorn (Figure 1). In the figure you can observe that at 180°C the critical temperature is achieved.

What makes the flakes?

Up to know we only know that pressure forces the kernel to break in order to release the steam generated inside the kernel. But how do popcorns acquire their nice flake shape?

Inside the popcorn endosperm, there are starch granules.

When the popcorns are heated, these starch granules expand adiabatically (Virot & Ponomarenko). This means that the expansion of the granules is done in conditions where there is no transfer of heat across the boundary (pericarp) of the thermodynamic system (inside of the kernel) and the surroundings (outside of the kernel).

This adiabatic expansion leads to a reduction of heat by a change in air pressure produced by volume expansion.

Hence, the volume expansion generates the characteristic spongy flake shapes of popcorns (Virot & Ponomarenko) (Hong & Both).

What makes the POP sound?

You might be already thinking that the POP sound comes from the explosion of the kernel while this is not the case. By looking at a snapshot of a popcorn while heated, it was discovered that the pop sound does not take place when the kernel exploits. Instead, the pop sound occurs when the water vapours generated inside the kernel was released and empty cavities are formed inside the kernel. Therefore, the pop sound are generated by these empty cavities which resonate once the pressure drops inside the kernel.

All popped popcorns are gymnasts

Scientists have compared popcorns with gymnasts (Virot & Ponomarenko). These active popcorns actually use a starch leg to propel themselves from the surface where they are placed on (our pans) (Figure 3).

Popcorns store elastic and thermal energy during its warm-up (heating process).

These energies are partially released as the kinetic energy of the starch leg. The energy used by the popcorns to jump is decrease by dissipative processes as the popcorn fracture or the POP sound generated (Virot & Ponomarenko).

Each popcorn is unique

Actually, when kernels are heated, the water contained inside becomes high temperature steam that makes starch to liquefy. Then, when the pressure inside the kernel arrives to its critical point, the starch which is in a liquid state bursts. The burst of the liquid starch is done through the kernel hull. As soon as the liquid starch its outside the kernel, it quickly cools down into a solid spongy flake (Schwartzberg, Wu, Nussinovitch, & Mugerwa). This is the main reason why there are no equal popcorns.

Each popcorn shape has hundreds to millions of small solidified starch bubbles whose location and size depends on the bursting of the liquid starch (Schwartzberg et al.).

Sometimes, if the heat is too high or unequally distributed, only a certain part of the kernel will burst.

During the bursting of a popcorn, the volume can be increased up to forty times and the kernel turns inside out (that is why the pericarp remains inside our spongy popcorns).

Hong, D. C., & Both, J. A. (2001). Controlling the size of popcorn. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 289(3), 557-560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(00)00542-2

Karababa, E. (2006). Physical properties of popcorn kernels (Vol. 72).

Schwartzberg, H. G., Wu, J. P. C., Nussinovitch, A., & Mugerwa, J. (1995). Modelling deformation and flow during vapor-induced puffing. Journal of Food Engineering, 25(3), 329-372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-8774(94)00015-2

Virot, E., & Ponomarenko, A. (2015). Popcorn: critical temperature, jump and sound J R Soc Interface (Vol. 12).

wawuuuuu, this is a fantastic discovery. you can’t imagine how much I m happy about this. I m also a biotechnologist, keep up guys ……

Cooogs