Falling chickens and the complexity of coral reefs

Day 3. Counting fish

We are ready to start diving with our group of eight scientists plus dive instructor Kirstin. At the diving deck we are queuing up with our regulators and fins in hand. Then the captain gives a sign and we jump into the water at a rapid pace, one by one from the side of the boat. As soon as I’m in the water I swim towards the buoy on my back and I take a bottle out of my net. After rinsing it a few times, I fill it with surface water, of which I will determine the nutrients later on board. Then I find my buddy Ayumi and we can descend with the rest of the group. On the reef, I swim behind my buddy who counts the fish, with fifty meters of measuring tape. When you roll out the reel you sometimes get surprised, I look up and … I’m face to face with a mega Caribbean lobster!

Caribbean lobster on the Saba Bank (photo: Oscar Bos)

The complexity of the reef

On the way back I measure the relief of the reef, by noting down the height of the coral every five meters. This way we get ten height measurements per transect of fifty meters. This is a measure of the complexity of the reef, or the number of hiding places for fish and other marine animals, or even for the nurse shark we encountered this morning. After this is done I take the second water sample at the seafloor.

Altitude measurements of the reef by Marin (photo: Oscar Bos)

Falling chickens

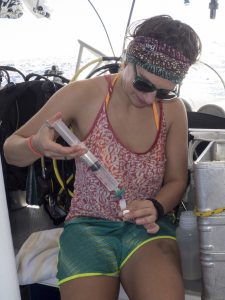

Filtering water for nutrients (photo: Oscar Bos)

Once out of the water, I process the water samples on deck. All our stuff is in a box that is tied to the boat. The wind and waves create an extra challenge: we have to be careful that no bags, caps and filters will be blown away. Fortunately, the box also protects us against the wind. We filter the water from the litre bottles, and transfer them into small tubes, which are further processed in the Netherlands. They have to fly back home frozen, so I join cook Julian in the galley and ask him if he can make room in the freezer full of food for our samples. You have to watch out that there is no frozen chicken falling on your head while you stow the sample tubes (upright) neatly. Then I quickly close the freezer again. Soon afterwards a big wave comes, and while the chopping boards and bowls are flying out of the kitchen cabinets, Julian catches the frying pan with hot oil in a reflex. This is next level cooking! Yet he ensures that every day a delicious meal is ready for us. And tonight’s desert: a warm brownie with chocolate ice cream!

Disco algae

In the dark we are anchored in the lee of the mountains of Saba, what a rest! In the light of the boat the tarpons – large silver fish with laser eyes – hunt for flying fish: strike! With a well-filled stomach we are back on the dive deck to get into those wet suits again for (possibly the only) fun dive of the week. The water bottles, slate and measuring tape now remain on board. During this night dive we are also treated with beautiful corals, sponges and all kinds of small animals. A giant basket star appears: a kind of starfish with thousands of curled tentacles. We turn our lamp the other way, away from the animal. In the dark, the flow between the tentacles creates a light show of disco algae!

Fishes and their shelters on the Saba Bank (photo: Oscar Bos)

Leadphoto: Basket star (type of starfish) (Photo: Erik Meesters)